Gandhiji’s assassination a few months after India’s freedom — and the accompanying brutality of Partition — tremendously disturbed Ram Narayanji, then based at Ajmer. India’s liberator and great mobilizer had been taken away but for Ram Narayanji, the loss was personal — that of a mentor and father figure. His faith in Gandhiji’s ideas of simple living, being truthful in life and nonviolence after Mahatma’s cruel murder only crystallized further.

Ram Narayanji, in Ajmer, continued with social work, writing and translation. By then, he had already published widely circulated newspapers in Hindi and English, viz. Rajasthan Kesari, Naveen Rajasthan, Navjyoti (weekly), Naya Rajasthan, and Young Rajasthan. Now he established himself as a scholar actively informing public discourse through his frequent columns in several dailies.

Ram Narayanji wrote over a dozen books in Hindi including a history of Rajasthan, experiences with Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, his wife Anjana Devi, and his thoughts on the future of Rajasthan. Some of his prominent books include Bapu: Meine Kya Dekha, Kya Samjha? (1954, Bapu as I saw him), an authorized and first-of-its-kind history of Rajasthan state titled Beesvi Sadi ka Rajasthan (1980, 20th Century Rajasthan), Vartmaan Rajasthan (1948, Present Rajasthan), among others.

In English, Chaudhary published his ideas on social work from his personal experience in a book titled Reflections of a Social Worker (1962). His popular and novel English books include Bapu as I saw him (1959, originally in Hindi), and a compilation of his interviews with Jawaharlal Nehru published in Nehru–In His Own Words (1964). Later, these two books were translated into Gujarati by Navajivan Trust and published as Bapu–Mari Najare and Panditji–Potani Vishe.

Ram Narayanji undertook the crucial task of translating over five dozen canonical texts of Gandhian literature written not only by Gandhiji but also other stalwarts such as Kaka Kalelkar, Mahadev Desai, Manu Desai, to name a few after India’s independence. The spectrum of these translation works is enormous: it includes Gandhi’s prison experiences at Yerwada jail, views on public education, ideas about state-society relations, caste system, natural remedies for diseases, and correspondence with Vallabhbhai Patel, ashram residents, among others.

Along with informing intellectual and public discourse, he did not lose sight of social work on the ground. For example, in the early-1950s, some Congress politicians developed crucial ideological differences with the orthodox and conservative elements of the party. They left Congress party en-masse and formed the Congress Socialist Party under the leadership of Ram Manohar Lohia.

Ram Narayanji had sympathies with this group as he shared their socialist and progressive vision and was equally distressed by factionalism in Congress party. He briefly joined this outfit but could not be accommodated at a senior position without causing discomfort to others — a fact brought to his notice by Lohia himself who tried to placate him. As Ram Narayanji was not interested in electoral politics, he chose to leave the outfit and provided guidance from the outside.

Just before the 1952 General Election, he was persuaded by Congress party to rejoin them. He respected this request and joined the party fold again but internal factionalism absolutely drew him away from electoral politics.

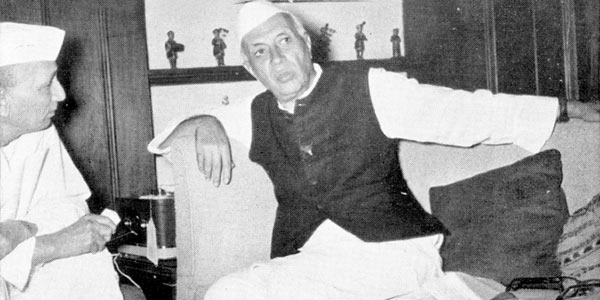

At this point, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, proposed to him to serve as information secretary in Bharat Sevak Sangh, a national development agency set up by the Planning Commission of India to aid the government’s development plans which were headed by Gulzarilal Nanda. Ram Narayanji had deep regards for Nehruji and was equally excited about working for the national cause. Consequently, he shifted to Delhi in 1955 to join Bharat Sevak Sangh acting as a key functionary handling constructive programmes, managing its correspondence and building awareness about the group. He did so for about five years.

In 1960, Ram Narayanji decided to establish a unique group to remove social evils and discriminatory traditions from society, improving skills of the poor and training bureaucrats and local sarpanchs. This organization was named as Gram Sahyog Samaj with its head-quarters in Faridabad on the outskirts of Delhi, mainly serving Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan region. Through Gram Sahyog Samaj, Ram Narayanji started a college in Faridabad’s Ajronda village which was named after Nehruji. This college trained over 5,000 bureaucrats and sarpanchs in just a decade in Punjab and Haryana.

Indeed, Nehruji had a crucial role to play in Ram Narayanji’s life in the decade-long period when he stayed in Delhi. Both of them had become good friends and met almost every week to discuss personal and political matters. They exchanged over 500 letters in this time! Ram Narayanji went on to interview Nehruji over nineteen different sittings in two years from 1958 to 1960 which have been published as Nehru–In His Own Words (1964).

Often, the Nehru government sought Ram Narayanji’s assistance on political issues. Nehruji wanted Ram Narayanji to serve in an official capacity and hold a political office. In 1952-53, he was offered the ambassadorship to Iran by the Indian government.

A few years later, Ram Narayanji was offered a ministership in the Nehru government. But true to his Gandhian ethic of maintaining distance from lucrative offices of power, Ram Narayanji refused both offers and helped the government only on a voluntary and pro bono basis. For example, Ram Narayanji acted as Indian government’s chief interlocutor with Shiromani Akali Dal’s leader Master Tara Singh who wanted a separate state of Punjabi speaking Sikhs in India. Ram Narayanji’s role was most crucial in taming this separatist demand in the formative years after India’s independence.